|

||||||

Kicking It Down

|

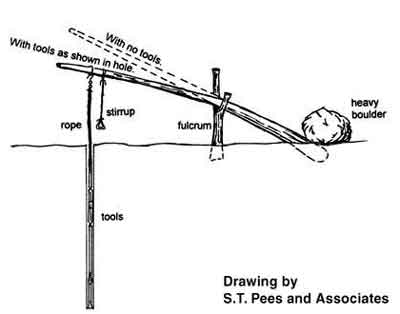

The principle which the spring pole employs is reciprocation. The downstroke is accomplished by leg power using the stirrup. The pole then springs back (reciprocates) to its normal position which depends on the weight of the drill string. |

A lot of wells were started with the spring-pole. This method required strong legs and considerable time. The outfit was simple: a long pole, a weight to anchor the butt end, a fulcrum, stirrup, manila rope, oak rods, downhole tools including the percussion bit. More tools and other improvements would be added to the drill string as time went on.

It was easy to get the pole. In the northern Appalachian basin the preferred wood was hemlock. It was springy and wouldn't crack easily. There were a lot of hemlock trees growing in the early oil region and still are. Ash and hickory were other trees that served well for spring poles. A tree would be selected to give about 30 feet or less of manageable pole and then cut and barked.

The fulcrum or fork was easy to make too. An oak tree would be found with a good limb and then cut to post size. The fork end would consist of a foot of sturdy trunk and a portion of the limb together forming a V. The post of the fulcrum would be firmly set into the ground and the spring-pole would be placed in the fork. The fulcrum would be positioned about a third (or less) distance from the butt end of the pole.

The pole's butt end would be anchored to the ground by boulders or a heavy log in such a way that the butt wouldn't move when the pole was springing. Sometimes wooden structures with a lintel and clamps would serve to secure the butt. All of these essential things could be found and fashioned in the forest, practically at the sites of the earliest oil wells.

The stirrup would hang from the spring-pole very near to the intended position of the borehole, maybe 3 1/2 feet to 4 feet from the working end of the pole. It could be a piece of manila rope looped at the bottom or it could resemble the stirrup on a saddle. The downward push of the driller's leg in the stirrup would bring the tip of the pole down and allow the bit to smack the rock. Sometimes two stirrups were used so that two men could work together.

The drill string (a vertical series of tools and components) would be fastened about 3 feet from the end of the pole. It would consist of manila rope or oak rods with metal connectors, rope socket, a sinker bar, jars, an auger stem and a bit. Manila rope could entirely replace the oak rods if desired, but the rods continued in common use in America into the 1860's, more or less. The augur stem was a 3 1/2 inch diameter solid iron bar up to 32 feet in length (most were shorter) with the box on the bottom into which the pin of the bit is screwed. The stem gives weight and some rigidity to the downhole operation. Additional cable tool drilling devices were put into use in the 1860's and later, but most reflected a background dating to the salt well days and to early water wells. Downhole tools will be discussed in a future chapter.

A high tripod of poles was erected over the borehole and pullies (sheaves) were hung from the apex of the tripod. This allowed the pulling of the drill string when tools needed to be changed or when the hole needed to be bailed out. The latter was done by a bailer tool which retrieved the accumulated cuttings and cavings and thus cleaned the hole prior to resumption of percussion (cable-tool) drilling. Later this tripod would become the derrick and constructed in that familiar manner.

|

The Drake Well Museum has a spring pole set up in the grounds for the amusement of the visitors. This photo shows the working end of the pole. Gerald English demonstrates how to kick it down. One day the author noticed that the well had reached a total depth of about 3 feet probably achieved by school children who arrive in bus loads to see the Museum. Later, workers demonstrated how a bailer works by hooking up the tool and retrieving the cuttings (and some gravel that fell in), thus cleaning out the hole. |

![]()

| © 2004, Samuel T. Pees all rights reserved |

|